The Quiet Ache of Work That No Longer Fits

Over the past 18 months, I’ve noticed a pattern—one that might feel familiar to many. It’s the sense that work, once meaningful or energising, has started to lose its spark. People across roles and career stages describe it differently: some feel stuck or dissatisfied, others want to grow but see no path forward, and many quietly ask themselves, “Is this really it?”

I’ve come to think of this as work entrapment, when the conditions, routines, and expectations around us subtly shape our choices and keep us in roles that no longer serve us. For some, work is simply a means to an end. For others, it’s deeply tied to identity and purpose. When that part of life stagnates, it can manifest as a slow, quiet ache, a gradual dimming of energy, like being a 100-volt light, but shining at only 20. What struck me most is how, over time, people adapt to these conditions, even when they no longer serve them.

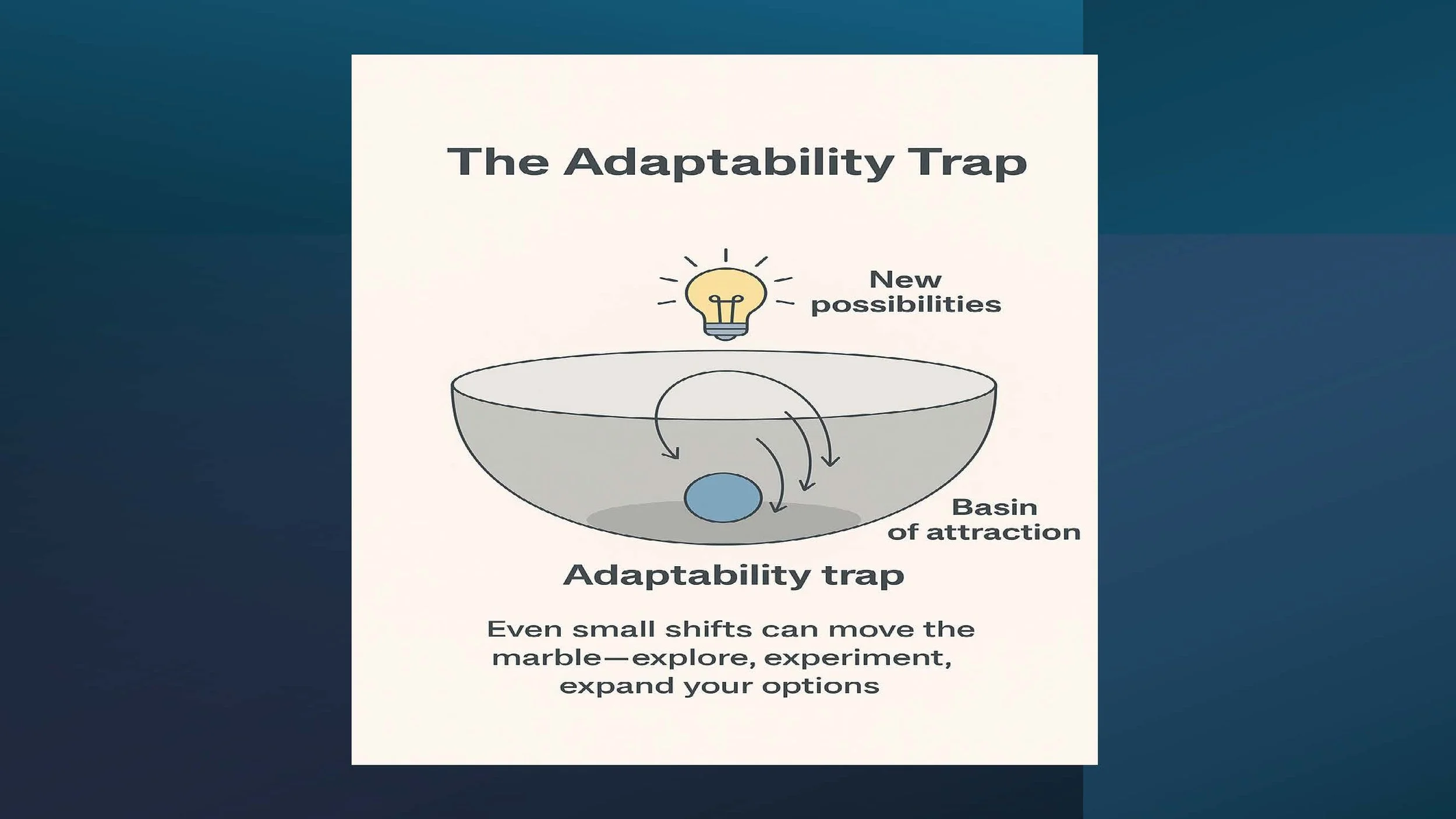

Because I think visually, an image comes to mind: a large bowl, with people trying to climb out, but without enough momentum to generate escape or create something new.

Through a complexity lens, this is the classic marble-in-a-bowl, a point attractor, a stable equilibrium that the system naturally returns to. Yet the overlooked part is the bowl itself. Its curved interior forms the basin of attraction, meaning that no matter where the marble starts, it eventually settles at the bottom. Different beginnings, same outcome.

Seen this way, work entrapment becomes easier to understand, not as a personal failing, but as the result of conditions that quietly guide us back to familiar patterns.

Many of the people I’ve worked with have successfully left those bowls that no longer served them, discovering that small shifts in perspective, habits, or environment can accumulate into meaningful movement toward more fulfilling and effective ways of working.

When Adaptability Keeps Us Stuck

It may seem counterintuitive, but being highly adaptable can sometimes keep us trapped in situations that no longer serve us. Instead of helping us move forward, our flexibility can stabilise the very circumstances we want to escape.

Here’s how this shows up:

Reframing challenges: We often tell ourselves, “It’s not that bad” or “This is part of learning.” While helpful in the moment, this reduces the urgency to make real change.

Routines and habits: We develop coping strategies that make our current situation easier to manage. Over time, these routines make it feel safer and harder to leave.

Identity as “resilient”: Seeing yourself as someone who can handle anything can make leaving feel like failing, even when change would be beneficial.

Tolerating more than we should: Each time we adapt to more challenging conditions, we expand what we consider “acceptable,” normalising discomfort.

Focusing on today: We often concentrate on solving immediate problems rather than exploring bigger possibilities, which narrows our view of what else is possible.

Reinforcement from others: People who adapt smoothly are rewarded—more responsibility, praise, and trust, which can make leaving feel costly or risky.

In everyday terms, adaptability can smooth over the pressures that might otherwise push us to change, making it easier to stay in the same situation, even if it no longer fits us.

The key: don’t abandon adaptability, redirect it. Use it to explore new options, try small experiments, and test alternative paths, rather than only keeping the current situation running smoothly. Preserve a little “useful discomfort” that sense that something isn’t quite right, because it’s often what motivates meaningful change.

Working With Systems, Not Against Them

Noticing the systems and patterns around you is the first step. Complexity concepts make visible the attractors and basins that guide our behaviour. By reflecting on where small, intentional experiments could expand your options, you can begin to move toward a more desirable state rather than just maintaining the status quo.

I’ve observed this happen for a number of people: with a bit of support and a few self-initiated, well-placed shifts in perspective, habit, or environment, what once seemed fixed begins to shift. There is real evidence that this is achievable. The path varies for everyone—there’s no single recipe or guidebook, timing differs, and ultimately, no one can do this work for you.

Call to Action

If, as you read this, you recognise yourself in these patterns, pause and ask:

Which conditions are shaping my choices and energy?

Where could small, deliberate experiments expand my options?

How might I redirect my adaptability to explore new possibilities rather than stabilising the current state?

By doing this, we can reclaim agency, expand options, and move toward work that truly aligns with our capabilities, values, and aspirations.

In a following article, I will explore how organisations can design systems that make these insights and opportunities more visible—helping teams and individuals navigate complexity and make adaptive, high-quality choices more frequently and with less friction.