When Retention Looks Good—but Isn’t: How Organisations Can Design for Choice, Not Constraint

In my last article, The Quiet Ache of Work That No Longer Fits, I explored why people can feel stuck even when nothing is “wrong on paper.” This new piece continues that conversation—shifting from the individual experience of entrapment to the organisational conditions that quietly shape it.

Today, I explore how organisations can design systems that make opportunities and insights more visible—helping people navigate complexity and make better choices with less friction.

When Organisational Design Creates Its Own Gravity

Sometimes an individual’s feeling of being trapped in a role is not about personal limitation; it’s about the system around them. In complexity terms, the organisation can behave like a basin of attraction, shaping the paths people take and the ones they stop seeing.

Some basins attract. Some confine.

The Paradox of Retention

Retention is usually celebrated as a success indicator. But in reality, retention has a paradox:

High retention can reflect a thriving workplace — or a quietly trapped workforce.

People may stay because they genuinely want to. Or because they feel they must.

And often, the data doesn’t tell you which.

Here’s how these patterns may show up:

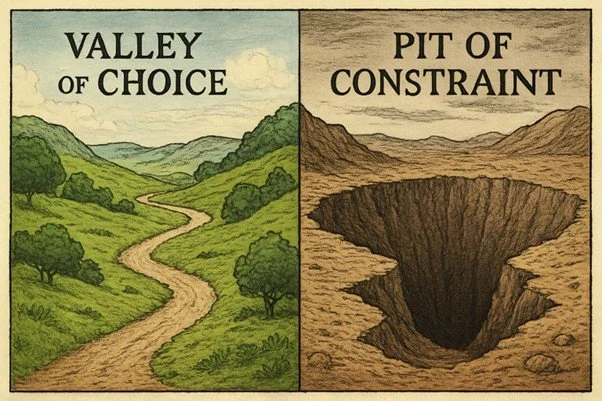

1. The Valley of Choice

People stay because they feel engaged, connected, and hopeful about their future inside the organisation. Retention here signals health.

2. The Pit of Constraint

People stay because they feel stuck. They may be:

burned out or too tired to look elsewhere

financially obliged to stay

held in place by overly specific skills or non-portable benefits

loyal to the point of self-sacrifice

adaptable people who keep being given “just a bit more” because they can absorb it

unable to imagine alternatives due to workload, fatigue, or diminished confidence

From a systems perspective, both are deep basins—but one is chosen, the other imposed. I think it's essential to understand which basin you are creating. Low turnover alone won’t tell you.

Why Intentions and Well-Being Matter More Than Turnover

A central reflection is simple but rarely asked:

Why do people stay? By choice—or by constraint?

Healthy retention tends to show:

high affective commitment

a sense of meaning

stable or improving well-being

curiosity, contribution, and stretch

Entrapment tends to show:

low affective commitment

high continuance commitment (“I can’t leave”)

declining energy and engagement

quiet depletion masked by reliability

These patterns rarely show up in dashboards. They show up in stories.

Why Surveys Aren’t Enough

Surveys give you numbers. But they rarely reveal the underlying dynamics that shape choice, constraint, or entrapment.

Metrics struggle to capture:

Why people stay

How power, pressure, or obligation influences decisions

Where friction is helpful vs. draining

The invisible/silent forces that shape movement inside a system

Narratives, however, reveal what surveys cannot. Stories uncover inflection points, subtle pressures, and moments when someone almost moved, but didn’t. They make visible what data hides.

This is how organisations begin to understand themselves as dynamical systems rather than static structures.

Helpful Friction vs. Unhelpful Drag

Not all friction is bad. Some friction is helpful, just enough tension, curiosity, or energy to create space for something new to emerge. It helps people pause, reflect, and reorient.

But unhelpful friction drains energy. It deepens the pit.

Distinguishing between the two is essential for designing environments where movement remains possible.

What Practically Makes a Difference

If the aim is to avoid the low-turnover/high-entrapment paradox, organisations can try to:

1. Strengthen commitment—personal and organisational: Go beyond alignment with organisational purpose. Help people stay connected to their own individual purpose and evolving interests.

2. Create real opportunities, not abstract encouragement: If you want people to grow a skill, give them the chance to use it. Application, not aspiration, is what changes trajectories.

3. Broaden development beyond current roles: Try not to confine development to what serves the current job. You can ask about other interests, assets, or emerging capabilities.

4. Have honest conversations about internal mobility: Not everyone can be the next team leader. If your structure is flat, define what “progress” means in reality.

5. Notice the roles where people often get stuck: Some families of roles, like sales, that have an easy point of entry, have high early mismatch rates. If someone realises it’s not for them, they need pathways, not guilt or more cheerleading.

6. Expand real and perceived options: Internal mobility, skill transferability, and external employability all reduce the sense of being trapped and without necessarily increasing exits.

7. Monitor intentions and health, not just exits: People can feel trapped long before they leave (or long before they admit it).

8. Redesign embeddedness toward choice, not constraint: Flexible arrangements, portable benefits, and life-fit design reduce unhealthy lock-in.

What You Can Do—Depending on Your Level of Influence

Not everyone holds the same power to reshape systems. But everyone can influence the environment around them.

At peer level: Stop reinforcing guilt-based retention (“don’t leave me here”). Encourage movement, not martyrdom.

As a team leader, create an environment where people feel comfortable sharing what's going on. And try not to force it. Use one-on-ones to understand people’s original stories, motivations, and paths—not just tasks and performance.

If you are gathering with your team, encourage them to work in pairs or trios and ask open-ended questions that invite reflection, such as: “What’s top of mind for you at the moment?” “What kind of choices do you see yourself making?”

Small-scale narrative inquiry reveals patterns you cannot access through formal processes. So if you influence budgets and systems, surveys are deeply embedded in organisational practice, but consider supplementing them with narrative approaches. Narratives don’t replace metrics—they humanise them.

Awareness doesn’t equal change. But it allows for new seeds to grow toward a coherent direction.

Takeaway Reflection

Organisations don’t set out to trap people. But without real attention, the combination of fatigue, loyalty, structure, and limited options can quietly deepen the pit of constraint.

By widening choice, listening to stories, and designing systems that support movement rather than dependence, those with enough power and willingness can transform retention from something measured into something meaningful.

If you can shift the conditions even slightly, such as more visibility, more possibility, more sensitivity, you help turn the organisational basin into something that supports people rather than holds them in place.